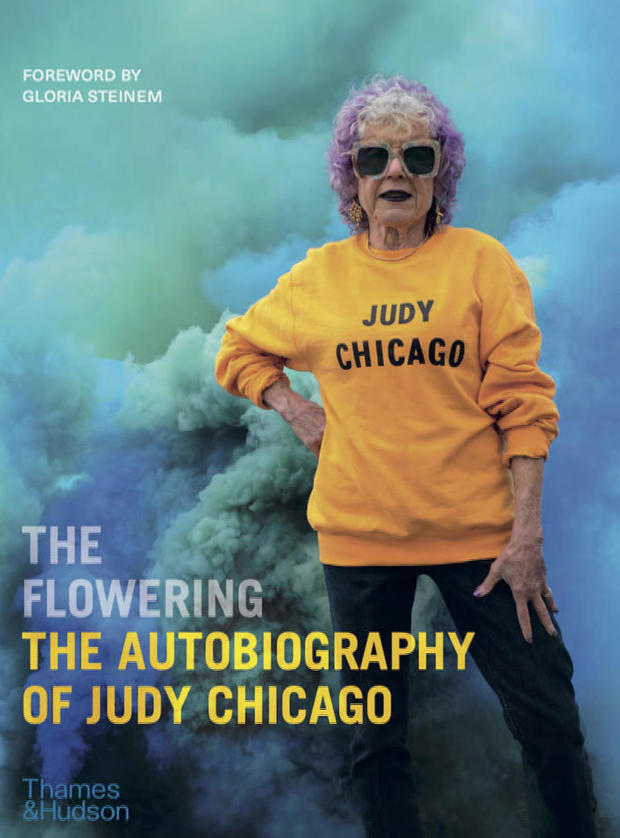

"The Dinner Party," a triangular table set for 39 singular women – Virginia Woolf, Sojourner Truth, and Georgia O'Keeffe among them – with the names of nearly a thousand others on the floor around it, in porcelain and needlework, has a spiritual, "Last Supper" quality, intentionally. "I wanted to substitute female heroes for male heroes," artist Judy Chicago said of her work. Women volunteers did the sewing. "All those anonymous stitchers in the ecclesiastical embroidery class making vestments in praise of male power, male deity – what if we took our own techniques and put them in service to our own achievements?" she told correspondent Martha Teichner. "It tells this story of centuries of struggle, achievement, erasure; struggle, achievement, erasure." Considered shocking and provocative when it was first shown in 1979, it was eviscerated by the critics (most of them male). One called it "vaginas on plates." Today, it is considered an icon of feminist art – since 2007, with pride of place in its own gallery at the Brooklyn Museum. Chicago said, "I used to go around saying, 'I wonder if I'll live long enough to see the body, huge body of my art, emerge from the shadow of 'The Dinner Party'!" A career retrospective at the de Young Museum in San Francisco is her first ever. She's 82, this woman acknowledged as the founding mother of feminist art. She said, "When I walked in, I got very emotional actually, because it was not just seeing the work, it was seeing my entire life." In the beginning, all she wanted was to be taken seriously as a woman artist: "I would watch these male artists, you know, being moved along on a little choo-choo train to success, and I would have a big show, and nothing would happen." Born Judith Cohen, she was married at 21 and a widow at 23 (her husband was killed in a car crash). Just out of graduate school, she threw herself into the southern California art scene, and tried to be "one of the boys." "I tried to look tough – I even tried smoking cigars for a while, but they didn't work, I was like (hacking)!" she laughed. By 1970, she'd had it. She declared her independence and affirmed her gender, and took a name of her own choosing: Judy Chicago, after her hometown. "I was not gonna hide who I was. I was just not." She became an artistic chameleon, matching technique to subject matter. She even went to auto body school to learn spray painting. The result: car hoods like no others. She tackled tough subjects: the extinction of animals; birth; toxic masculinity; the Holocaust. Teichner asked, "A lot of artists don't do 10, 15 techniques in a lifetime. They do one or two." "I'd be bored," said Chicago. "I would shoot myself." She and her husband, Donald Woodman, live and work in an old hotel Woodman renovated in Belen, New Mexico, an out-of-the way railroad town south of Albuquerque. They've been married since 1985. Woodman is a respected photographer but also a collaborator on his wife's projects. Here, Judy Chicago exists in a kind of exile from the hostility of the art establishment. "Anger can fuel creativity," she said. "And in my case, it did. I had a burning desire to make art. That was what was the most important thing to me in my life. I gave up everything for it. I don't care. That was my goal." But a funny thing happened: Times changed. A #MeToo world finally "got" Judy Chicago. Suddenly she was a star. She designed the set for the 2020 Dior Couture show in Paris, and a line of Dior handbags. Last summer, Chicago published an autobiography, "The Flowering," just in time for the opening of the de Young show. The exhibition begins with "The End," her most recent series ("I think one of the things that actually makes life meaningful is the fact that it's going to end"), so viewers have no choice but to take in the breadth of what Judy Chicago has done other than "The Dinner Party." "And then they'll come into this room and they'll go, thank God!" Chicago laughed. "Pastel color and light!" "Right, that and abstraction!" She's always loved color. Her favorite is purple (you'd never guess). On a perfect mid-October evening, outside the de Young Museum, she set off an explosion of color. The non-toxic smokes billowed and blended, as thousands of fans watched art blowing away. Cheered on by the world at her feet, art world be damned, for Judy Chicago validation, after all this time looks like this. For more info:

Story produced by Julia Kracov. Editor: Remington Korper.

Tags:

News